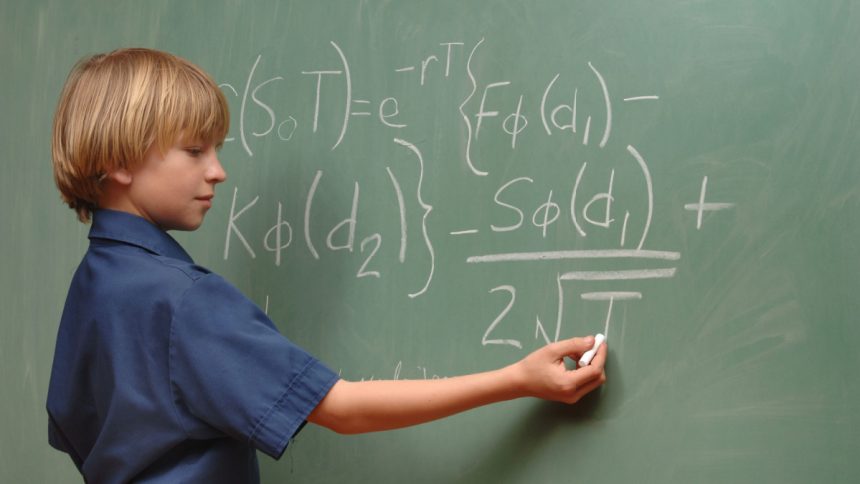

Teaching a child strong math fundamentals is vital for their ability to navigate the personal, social, and political challenges of the future.

Professor Kim Beswick, Director of the Gonski Institute and Head of the School of Education at the University of New South Wales (UNSW), says maths is more than just numbers and symbols; it’s a critical part of our everyday lives, and developing those skills in our young people is crucial for them to navigate complex issues.

“Mathematical practices are fundamental to navigating our everyday lives,” she says.

“Maths helps us make well-founded judgements about all sorts of [day-to-day] things, including food, distance and time, costs, loans, and sports, which need to be considered in the context of other considerations and priorities. Few decisions are purely mathematical; they have individual and societal impacts beyond the maths that must be considered.”

COVID-19 and climate change are among many issues that indicate a rapidly evolving and disruptive world for young people, highlighting the importance of developing their problem-solving skills.

“We constantly hear data about different elements of our lives, from accelerating rates of global warming to the prevalence of vaping and its health risks,” Professor Beswick says. “If people don’t understand the maths, or they’re not confident in it, they can’t engage sensibly in conversations about what might or might not be effective [interventions] or understand the degree of [their] personal risk.”

Maths teaching needs to be about more than skills and routine problems

The OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) indicate that Australian students find mathematical reasoning complex compared to other countries.

“This highlights the urgent need to address teaching practices that promote students’ critical maths thinking within Australian schools,” says Professor Beswick. “What happens way too often is that students learn the routine algorithmic material – they understand the processes that get the correct answers, they can solve equations, for example – but usually when it comes to some real-life problem, they avoid maths.”

It’s essential to teach maths so that children understand its first principles “to make sure they can make sense of the calculation, as well as knowing how to do the calculation, and that will help them make sense of the world”, she says.

“There are great teachers who do just that, but it doesn’t happen nearly enough. International studies that ask students about what goes on in the classrooms depict a very traditional approach to lessons in Australia.”

Critical thinking is best developed in relatable scenarios

Professor Beswick says students, when confronted with critical mathematical thinking problems, excel in scenarios that are relatable and recognisable as something real people face.

“For example, when we asked a class of high school students in Brisbane to consider whether or not residents of flood-affected areas should take up the government’s offer to buy back their properties, they could see, mathematically, that the buyback was a good deal, but realised there were other considerations,” she says.

“Can I find somewhere to buy that is not flood-prone and still close enough to work? How will it affect social networks? What childcare and school options are available in an area I could move to? These things affect different individuals differently, so there is not one correct answer. Of course, real life is messier than maths problems, but critical mathematical thinking encourages kids to consider the assumptions made and their limitations – that’s the critical thinking part.”

Engaging with complicated problems supports critical math thinking

In Australia, we often teach shorter math problems; Professor Beswick recommends that we adopt a similar approach to those in Japan – focusing more on more significant issues that require more critical thinking.

“Moving in that direction would be useful so kids can delve into the problem and what’s going on there and make sense of it for themselves,” she says. “A good teacher can guide in-class discussion about an interesting problem so children don’t waste time following dead ends and get frustrated. They develop deeper insights and make connections among maths ideas and between those ideas and the ways they can be used.”

Professor Beswick is partnering with a team of national and international experts on an Australia Research Council (ARC) project, Enabling students’ critical mathematical thinking.

It aims to generate new insights into teaching practices that may improve critical mathematical thinking outcomes for students.

“Focusing only on the maths, separate from its applications, results in students thinking maths is irrelevant and, for too many, not something they want to pursue,” Professor Beswick says.

“It means that students might spend a whole lesson on one problem or issue or maybe longer. But they will have learned [the concepts involved] in a much deeper way. Practicing skills is important, but when students understand the relevant concepts, less is needed.”

Beliefs around student capability can influence teachers’ approaches

Professor Beswick says a teacher’s impressions of student capability affect the outcomes.

“People close doors to students … Too often, they get classified rather than taught. The answer is to move them down a level rather than help them make up what they might have missed or explain things another way,” she says. “I’d be the first to say there is also value in learning pure maths,” she says.

Pure maths, she says, should be seen as like art or music, and something that is a part of our cultural heritage.

“It can be a thing of beauty – and not everyone’s going to enjoy it or appreciate it, but they should be allowed to access it as part of our culture,” she says.

“For most students, seeing the way maths can be used to help individual and societal decision-making will be what inspires them to study the subject.”